- Home

- Beezy Marsh

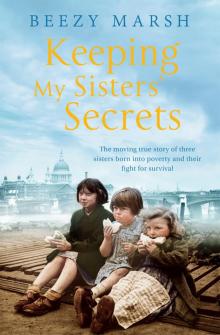

Keeping My Sister's Secrets

Keeping My Sister's Secrets Read online

Keeping

my Sisters’

Secrets

BEEZY MARSH

PAN BOOKS

To the memory of Londoners

who lost their lives in the Second World War.

Contents

Prologue: 1931

1: Eva, May 1931

2: Peggy, August 1931

3: Kathleen, February 1932

4: Eva, March 1932

5: Peggy, October 1932

6: Kathleen, March 1933

7: Eva, May 1933

8: Peggy, August 1933

9: Kathleen, October 1933

10: Eva, February 1934

11: Peggy, July 1934

12: Kathleen, October 1934

13: Eva, December 1934

14: Peggy, January 1935

15: Kathleen, May 1935

16: Eva, January 1936

17: Peggy, February 1936

18: Kathleen, May 1937

19: Eva, October 1937

20: Peggy, January 1938

21: Kathleen, April 1939

22: Eva, November 1939

23: Peggy, May 1940

24: Kathleen, November, 1940

25: Eva, March 1942

26: Peggy, September 1943

27: The Lambeth Girls, May 1945

Epilogue: 1949

Acknowledgements

Prologue

1931

The grimy streets of Lambeth, nestled beside the river Thames, had changed little since the days of Charles Dickens, when the poorest working classes lived cheek-by-jowl with thieves and drunkards. Women living there took in piece-work such as laundry or fur-pulling to help make ends meet, just as their mothers and grandmothers had done before them. Their husbands worked long hours, either in the factories as labourers, as costermongers or down at the docks. And that was if they were lucky enough to have their men in work. Families were large – five or six children, or more – and diseases including scarlet fever and diphtheria were fatal and much-feared. The threat of poverty was ever present but the temptation for husbands to drown their sorrows in one of the many local pubs could lead to the whole family being thrown out into the street when the rent- and tallyman came knocking for their dues.

These little rows of two-up, two-downs were tight-knit communities where scores were sometimes settled with fists. The police would only venture down there in pairs and rarely after nightfall when the dim glow of gaslight did little to illuminate pea-souper fogs. Yet for those growing up in this corner of Lambeth, the cobbled streets, the stench of the river, the shouts of the factory workers, the nosy neighbours and the rumble of the trains over at Waterloo meant one thing – home.

This is the story of three sisters growing up in one such street, Howley Terrace, in the years between the wars. It is the story of their hopes and dreams and struggles for a better life when the odds were stacked against them.

This is the story of the Lambeth girls, Peggy, Kathleen and Eva, who learned to keep each other’s secrets in a bond of sisterhood, which even dire poverty, violence and war could not break.

1

Eva, May 1931

She didn’t really mind getting up so early.

Eva could hear her father downstairs in the scullery, clattering about making himself a pot of tea before work. It was barely light outside but if he didn’t leave the house soon, she’d miss all the best buns at the bakery over in Covent Garden.

Eva waited until she heard him pulling on his boots and the front door slam shut before she forced her feet out of her warm nest in the flannelette sheets and onto the bare boards of the bedroom floor. Kathleen, her sister, lay next to her, soundly asleep. Her hair was tied in rags, which spread out on the pillow like little snakes. Mum didn’t bother putting Eva’s hair in rags. ‘Dead straight, like your father’s,’ she told her. ‘There’s little or no point trying to make it curly.’ Kathleen, on the other hand, had near-perfect ringlets even without the help of mother and her nightly rag-ties. Eva toyed with the idea of yanking one of those raggy little tails but thought better of it. She didn’t want to wake the whole street with Kathleen’s squealing.

Instead, Eva grasped her own thick, long black hair and tied it with a grubby ribbon before pulling on her pinafore and making her way out onto the landing. Mum, already dressed in her housecoat and slippers, was standing there, holding out a pillowcase for her.

‘Mind he doesn’t see you,’ she whispered.

Eva took the pillowcase and nodded solemnly. If Dad knew what she was up to, it would earn her a belting, not that she cared. She’d felt the buckle end of his belt on more than one occasion. The welts went down after a while and all that remained was an empty feeling inside, which was worse than hunger. At least bread made her feel a bit better. Day-old bread from Godden and Hanken bakery was a mainstay of their diet and a cheap way for Mum to fill their rumbling bellies when the housekeeping was running short – which was most of the time, these days. But Eva’s father wouldn’t tolerate her queuing up for handouts with the children from the Thieves’ Kitchen of the Seven Dials, like some common urchin.

Eva was eight, nearly nine in fact, so she was too young to go out to work but she would have done if she could, just to help Mum. She was the youngest after Frank but was more daring than any of her brothers and sisters. Kathleen would soon be eleven and she should really have made the trip but liked her sleep too much to bother, same as her twin, Jim. Peggy was thirteen and would be leaving school in a year or so but she was a goody-two-shoes, Dad’s favourite, and wouldn’t dare do anything to risk his anger.

The early mornings were making Eva tired and she was prone to catching forty winks in the afternoons during lessons. Her teacher at St Patrick’s had said as much when she met her mother on the Walworth Road last week: ‘Eva really does need to get to bed earlier, Mrs Fraser!’

Eva hurried down their tiny street, each house with the same two storeys of grimy bricks as the last, before turning left onto Waterloo Bridge. She knew the route by heart: up Bow Street, into Long Acre and over to Great Newport Street.

Flower sellers in long skirts and straw hats, their woollen shawls pulled tightly around their shoulders, were already at their pitches and the drunks from the night before were still lying in the gutter as Eva ran the last hundred yards to the bakery door. She was the last one there. A row of ragged children, some with dirty faces and no shoes, jostled in front of her, brandishing their pennies.

Eva drew herself up to her full height and flicked imaginary dust off her pinafore as she looked down her nose at them. Yes, she was poor but she was clean; Mum always made sure of that, even though Eva hated having her face wiped with a dishcloth before she left the house. The tin bath took pride of place in the scullery once a week and she got her turn in it. She scratched her head. Nits again, probably, but Mum would sort that out with a metal comb later. Eva winced at the thought of her hair being pulled and scraped. She sighed as she waited her turn, the penny in her hand growing sweaty. What if there was nothing left for her to take home?

Dad had a good job as a wood sawyer down at the cricket bat factory but with five of them to feed on wages of two pounds a week, there just wasn’t enough to go around. It was all their mother could do to keep shoes on their feet. Frankie’s were full of holes, mainly because he was the youngest and got all the hand-me-downs. And that was before Mum got to paying out the ‘insurances’. Eva didn’t fully understand what they were but it was to do with the hospital and teeth and the like. Mum said, ‘Don’t worry your head about it, chicken,’ but Eva did worry. Especially when she saw her mother twisting her thin gold wedding band round and round her finger and her eyes red-rimmed from crying when all the money ha

d run out by Wednesday.

The insurances had seemed to go up after Frankie got run over by a lorry a couple of years back. Eva swallowed hard at the memory of it. She was supposed to be minding him while Mum went out to clean at one of the little hotels up by Waterloo Station to earn a few pennies more. She had another job in the mornings cleaning over at the Imperial Chemical Industries building but that didn’t pay enough.

It had all happened so fast. They were playing in the streets with the other kids from Howley Terrace, larking about. Someone had a dog which had caught a rat and they poked at the dead body a bit with some sticks and watched it ooze blood. ‘Massive teeth,’ said one boy. ‘Like yer grandad!’ said Frankie, poking him in the ribs and making everyone hoot with laughter.

Frankie got bored of it all in the end. Kathleen turned her nose up and went to go skipping with Doreen from a few doors down. Peggy had her head stuck in a book, as usual, and was sitting on the front step, reading. Eva was only chatting to her pal, Gladys, for an instant about the new clothes her Nanny Day had knitted for her peg dolly, which made her look so pretty. Then she heard Frankie shout: ‘Got any cards, mister?’ just as one of the lorries from the wastepaper factory at the top of the road came trundling past.

‘Frankie! Wait!’ Eva called, but he didn’t hear and ran forwards, hands outstretched, as the driver chucked a few cigarette cards out onto the cobbles. Frankie bent down to pick them up without noticing a second lorry following close behind. Eva screamed. Then she ran. It was too late. Frankie disappeared under the wheels and there was the most horrible sound. The driver did his best to stop but couldn’t and Eva watched in horror as Frankie’s broken body emerged at the other end of the truck.

Women came running from the terraced houses and it suddenly seemed the whole street was there, watching Frankie’s little body, his head crushed and bleeding, oozing onto the greasy cobblestones, his eyes closed, his face white as a sheet.

The driver got out of the cab, shaking: ‘Oh my God!’ He turned to the crowd and pleaded with them as the mood changed from shock to anger. ‘Me brakes don’t work that quick, see?’

Eva knelt down beside Frank to help, but the grown-ups were already loading him onto the tailgate of the lorry and it was off to St Thomas’s Hospital. Peggy ran to get Mum from her cleaning at the hotel and Kathleen and Jim ran a mile to Stuart Surridge’s factory to get Dad. Eva clung to Frankie on the back of that lorry, sobbing, as Mrs Avens from a few doors down tried to shush her and tell her to let go of him but she wouldn’t. The doctors had to prise her off Frankie when they got to the hospital. They rushed him off on a stretcher, away through the double doors, his head swathed in bandages.

Then Nanny Day came to the hospital with Mum crying. Dad, looking ashen, his hands thrust into his coat pockets, rushed past Eva. Nanny Day, still wearing her best white apron over her long skirts, took Eva from Mrs Avens’s arms and held her hand. ‘Now, don’t be fretting about it or blaming yourself,’ she told Eva, her bright blue eyes shining with tears. ‘The good Lord will protect our Frankie, just you wait and see.’ She crossed herself. ‘Come on, Eva, let’s get you back indoors.’

Nanny Day walked the half-mile back along Belvedere Road, past the Lion Brewery and the factories, clasping Eva’s hand the whole time. Eva had been terrified of that lion statue when she was smaller, and Nanny Day still joked about it jumping down and gobbling her up, when she was naughty. It was a huge beast, looming high above the brewery gate, its body blackened by soot but its face still peering majestically into the distance. Now she was a bit older, whenever she walked past Eva pondered how long it must have taken someone to carve him. She still joined in the fun when Nanny Day had a joke with them about going on a lion hunt.

There were no jokes today. When they got to Howley Terrace, the neighbours were sitting out on their steps, waiting. Some had even brought chairs out and, from the look on their faces as Eva and Nanny Day walked by, the accident was the chief topic of conversation. A couple of them started to approach but Nanny Day cut right through, like a ship in full sail, and took Eva through the front door.

Eva picked up her dolly and her nightdress and Nanny Day took some tea from the caddy and put it in a brown paper bag, which Mum kept neatly folded in the single drawer of the kitchen table. She was running a bit short at home and extra supplies of Nanny’s strong brown tea with a splash of evaporated milk would be needed to keep everyone’s spirits up. The street fell silent as they emerged from number 6 Howley Terrace. Eva pulled the door shut. They didn’t lock it – there was nothing worth stealing, and in any case, people kept an eye out for each other in their neighbourhood. Rather too much, in her father’s opinion: ‘A right nosy lot.’

The murmurs about how Frankie was doing and whether he would pull through died away as they walked back down Howley Terrace, into Tenison Street and across Waterloo Road and into Cornwall Road, to Nanny Day’s house. The blood was still rushing in Eva’s ears at the thought of the accident but coming to her grandparents’ house calmed her at last. All the children had been born here, at 100 Cornwall Road, and Eva loved coming to stay because she got to have bread and dripping whenever she liked, even if Grandad did tell her to sling her hook when she pestered him for another piece, toasted on the open fire.

Today was different. After a mug of cocoa she was tucked up in Nanny Day’s bed with Kathleen and Peggy already there and sleeping soundly. Jim had already nodded off in the rocking chair in the front room. Eva fell almost instantly into a deep sleep. ‘Shock,’ she heard Nanny Day whisper to Grandad, just as she was drifting off. He was standing on the landing outside, wondering if he was going to have to kip on the sofa again because his leg was bloody killing him and he would have preferred a proper bed for the night, even though he loved those little urchins dearly.

The girls didn’t see their parents for nearly a week and the routine of getting up, going to school and coming home and avoiding Grandad – ‘Gertcha!’ – was interspersed with visits from the parish priest. Eva took to hiding under the kitchen table to eavesdrop as it was the only way to find out how her beloved little brother was getting on. Nanny Day would always cover the table with her best white linen tablecloth on days when the priest was due. It hung almost to the floor and Eva concealed herself underneath the table, quiet as a mouse, and marvelled at the father’s highly polished shoes, which must surely have come from heaven itself, they were so clean and shiny.

At first, Eva thought she was being punished by her parents’ absence but little by little, through the grown-up talk she overheard at the kitchen table, as she sat hugging her knees and hardly daring to breathe, she found out it was because Frankie was so sick. His head had swelled to twice its size and they had to pack it in ice and then he got an infection called meningitis which made everything hurt badly.

After a fortnight she was allowed to go on a visit. Only for a few minutes and there was no question of everyone going because the hospital was very strict about overexciting him. The smell of disinfectant hit her first. The floor was lino, polished so much you could almost see your face in it. There was a table in the middle of the ward with flowers in a vase and children all pale, propped up in bed like little soldiers, for visiting time. All except Frankie, who was allowed to lie back on one pillow, on account of his head injury. ‘Hello, Eve,’ he murmured, and Eva squeezed his hand. He was like Frankie, only a lot thinner, with a bigger head and a bandage on it.

The nurses wore crisp white uniforms and smelt of starch and only one of them smiled. Every time she went there Eva knew in her heart that it was all her fault. She swore then to protect Frankie and do everything she could to make him well. Getting the bread every day to help Mum was part of it. He did get better but he was never quite the same again.

She felt something poking her in the ribs, bringing her back to reality. It was a little girl with scruffier plaits than her own, and big rip in her pinafore. ‘It’s your turn next,’ she said, looking up at Eva with beady eyes. �

��Get a move on, will yer?’

Eva tutted at her but shuffled forwards to take her place at the head of the queue, glad that the wait was over. Her stomach rumbled loudly.

The baker, a big fella, still had a crate full of day-old buns and loaves to get rid of. She handed over her penny and opened her pillowcase, praying he would fill it right up for her. She was one of his regular early-morning customers and he gave her a wink as he slipped a jam tart in there, for her to munch on the way home. Eva winked back at him, grateful as ever for his kindness.

Eva emerged triumphantly from the shop with her pillowcase stuffed to the gunnels. She heard the clock strike half past the hour as she sat down on some steps to devour the jam tart. Costermongers were wheeling their barrows out in Covent Garden, and the shouts which marked the start of the working day filled the air.

She’d be home in plenty of time to give the others their breakfast and she’d make sure Frankie got one of the best buns. Eva crossed back over Waterloo Bridge, heading for home, swinging her pillowcase as she went. A row of railway arches lay under the bridge, opposite the yards of her street, and the hotels above them would sometimes chuck their rubbish on the people living down below. The rats were already making themselves busy finding something to eat. Eva watched them for a second, instinctively clasping her pillowcase a little tighter as she watched the longtails rootling about in a heap of vegetable peelings and old chicken bones. Everything in their street, on four legs or two, was always on the hunt for food.

Getting the bread was one thing, but Eva knew there must be other ways to help Mum and her family – and she was determined to find them.

2

Peggy, August 1931

From her vantage point on the front doorstep, Peggy had made a secret study of the way the women moved up and down the street. Clasping the book in her hand seemed to make her invisible in Howley Terrace, apart from the jeers of ‘bookworm’ from her younger sisters and some of their silly little street friends. She read endlessly: books borrowed from the public library and her most treasured, on loan from her teacher, Mrs Price, who recognized her pupil’s love of learning but knew that the family budget would not extend to buying literature.

Her Father's Daughter

Her Father's Daughter Queen of Thieves

Queen of Thieves Keeping My Sister's Secrets

Keeping My Sister's Secrets All My Mother's Secrets

All My Mother's Secrets